March 331 1963 Arts of Southern California Xiii Painting

| Whaam! | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Roy Lichtenstein |

| Twelvemonth | 1963 |

| Medium | Magna acrylic and oil on sail |

| Movement | Pop art |

| Dimensions | 172.7 cm × 406.4 cm (68.0 in × 160.0 in) |

| Location | Tate Modern, London |

Whaam! is a 1963 diptych painting by the American artist Roy Lichtenstein. It is one of the best-known works of popular fine art, and amidst Lichtenstein'due south most of import paintings. Whaam! was first exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City in 1963, and purchased past the Tate Gallery, London, in 1966. It has been on permanent display at Tate Modern since 2006.

The left-manus panel shows a fighter plane firing a rocket that, in the right-manus panel, hits a 2nd plane which explodes in flames. Lichtenstein conceived the image from several comic-volume panels. He transformed his master source, a console from a 1962 war comic book, by presenting information technology every bit a diptych while altering the relationship of the graphical and narrative elements. Whaam! is regarded for the temporal, spatial and psychological integration of its two panels. The painting'southward title is integral to the action and bear upon of the painting, and displayed in big onomatopoeia in the right panel.

Lichtenstein studied as an artist before and afterward serving in the United States Army during World War II. He practiced anti-aircraft drills during bones training, and he was sent for pilot training but the programme was canceled before it started. Amid the topics he tackled after the war were romance and war. He depicted aerial combat in several works. Whaam! is function of a serial on war that he worked on between 1962 and 1964, and forth with As I Opened Burn (1964) is one of his two large war-themed paintings.

Background [edit]

In 1943 Lichtenstein left his study of painting and cartoon at Ohio Country University to serve in the U.South. Army, where he remained until January 1946. After entering preparation programs for languages, engineering, and piloting, all of which were canceled, he served as an orderly, draftsman and artist in noncombat roles.[one] [two] I of his duties at Camp Shelby was enlarging Bill Mauldin'southward Stars and Stripes cartoons.[one] He was sent to Europe with an engineer battalion, but did not see agile combat.[one] As a painter, he eventually settled on an abstract-expressionist mode with parodist elements.[3] Around 1958 he began to contain hidden images of cartoon characters such as Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny into his abstruse works.[iv]

A new generation of artists emerged in tardily 1950s and early on 1960s with a more objective, "absurd" approach characterized by the art movements known today every bit minimalism,[5] hard-edge painting,[6] color field painting,[7] the neo-Dada motion,[8] Fluxus,[9] and pop art, all of which re-divers the avant-garde contemporary art of the fourth dimension. Pop art and neo-Dada re-introduced and changed the utilise of imagery past appropriating subject affair from commercial art, consumer appurtenances, art history and mainstream civilization.[10] [11] Lichtenstein achieved international recognition during the 1960s as ane of the initiators of the pop art movement in America.[12] Regarding his employ of imagery MoMA curator Bernice Rose observed that Lichtenstein was interested in "challenging the notion of originality equally it prevailed at that time."[13]

Lichtenstein's early on comics-based works such as Look Mickey focused on popular animated characters. By 1963 he had progressed to more than serious, dramatic subject area affair, typically focusing on romantic situations or war scenes.[14] Comic books as a genre were held in low esteem at the time. Public antipathy led in 1954 to examination of alleged connections between comic books and youth crime during Senate investigations into juvenile malversation;[15] by the end of that decade, comic books were regarded as fabric of "the everyman commercial and intellectual kind", co-ordinate to Marker Thistlethwaite of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.[fifteen] Lichtenstein was non a comic-volume enthusiast every bit a youth,[16] but was enticed as an artist by the claiming of creating art based on a subject remote from the typical "artistic image".[17] Lichtenstein admitted he was "very excited most, and very interested in, the highly emotional content nevertheless discrete impersonal handling of love, hate, war, etc., in these cartoon images."[xiv]

Lichtenstein'southward romance and war comic-based works took heroic subjects from small source panels and monumentalized them.[eighteen] Whaam! is comparable in size to the generally large canvases painted at that fourth dimension by the abstruse expressionists.[nineteen] Information technology is one of Lichtenstein's many works with an aeronautical theme.[twenty] He said that "the heroes depicted in comic books are fascist types, but I don't have them seriously in these paintings—perhaps there is a point in non taking them seriously, a political point. I use them for purely formal reasons."[21]

History [edit]

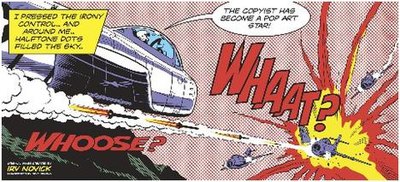

Whaam! adapts a panel by Irv Novick from the "Star Jockey" story from event No. 89 of DC Comics' All-American Men of War (February. 1962).[22] [23] [24] The original forms part of a dream sequence in which fictional World War Ii P-51 Mustang pilot Johnny Flying Cloud, "the Navajo ace", foresees himself flying a jet fighter while shooting down other jet planes.[25] [26] In Lichtenstein'southward painting, both the attacking and target planes are replaced by different types of aircraft. Paul Gravett suggests that Lichtenstein substituted the attacking airplane with an aircraft from "Wingmate of Doom" illustrated by Jerry Grandenetti in the subsequent issue (#90, April 1962),[27] and that the target aeroplane was borrowed from a Russ Heath[28] drawing in the 3rd panel of page 3 of the "Aces Wild" story in the same issue No. 89.[27] The painting also omits the speech chimera from the source in which the pilot exclaims "The enemy has go a flaming star!"[29]

A smaller, single-panel oil painting by Lichtenstein around the aforementioned fourth dimension, Tex!, has a similar composition, with a plane at the lower left shooting an air-to-air missile at a second aeroplane that is exploding in the upper right, with a word chimera.[xxx] The aforementioned outcome of All-American Men of War was the inspiration for at least iii other Lichtenstein paintings, Okay Hot-Shot, Okay!, Brattata and Blam, in addition to Whaam! and Tex! [31] The graphite pencil sketch, Jet Pilot was also from that effect.[32] Several of Lichtenstein's other comics-based works are inspired by stories about Johnny Flying Cloud written by Robert Kanigher and illustrated by Novick, including Okay Hot-Shot, Okay!, Jet Pilot and Von Karp.[26]

Lichtenstein repeatedly depicted aeriform combat between the United States and the Soviet Union.[2] In the early and mid-1960s, he produced "explosion" sculptures, taking subjects such as the "catastrophic release of energy" from paintings such every bit Whaam! and depicting them in freestanding and relief forms.[33] In 1963, he was parodying a variety of artworks, from advertising and comics and to "high fine art" modern masterpieces past Cézanne, Mondrian, Picasso and others. At the time, Lichtenstein noted that "the things that I have apparently parodied I actually admire."[34]

Lichtenstein's showtime solo exhibition was held at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York Urban center, from 10 Feb to 3 March 1962. Information technology sold out before its opening.[35] The exhibition included Look Mickey,[36] Appointment Ring, Blam and The Refrigerator.[37] Co-ordinate to the Lichtenstein Foundation website, Whaam! was office of Lichtenstein'due south 2d solo exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery from 28 September to 24 October 1963, that likewise included Drowning Daughter, Baseball game Manager, In the Car, Conversation, and Torpedo...Los! [1] [35] Marketing materials for the show included the lithograph artwork, Crak! [38] [39]

The Lichtenstein Foundation website says that Lichtenstein began using his opaque projector technique in 1962.[i] in 1967 he described his process for producing comics-based art as follows:

I do them as direct as possible. If I am working from a cartoon, photograph or whatever, I depict a small movie—the size that will fit into my opaque projector ... I don't depict a film in order to reproduce it—I do it in order to recompose information technology ... I become all the style from having my drawing virtually similar the original to making it up altogether.[twoscore]

Lichtenstein may accept substituted this paradigm for the attacking plane from the subsequent issue of DC Comics' All-American Men of War No. xc (Apr 1962).

Whaam! was purchased past the Tate Gallery in 1966.[1] In 1969, Lichtenstein donated his initial graphite-on-paper drawing Cartoon for 'Whaam!' , describing it every bit a "pencil scribble".[41] According to the Tate, Lichtenstein claimed that this drawing represented his "first visualization of Whaam! and that it was executed simply before he started the painting."[42] Although he had conceived of a unified work of fine art on a unmarried canvas, he made the sketch on two sheets of paper of equal size—measuring 14.nine cm × 30.5 cm (5.nine in × 12.0 in).[42] The painting has been displayed at Tate Modern since 2006.[43] In 2012–13, both works were included in the largest Lichtenstein retrospective nonetheless exhibited, visiting the Art Found of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Tate Modern in London and the Centre Pompidou.[44]

Description [edit]

Whaam! depicts a fighter aircraft in the left panel firing a rocket into an enemy plane in the right panel, which disintegrates in a vivid cherry-and-yellow explosion. The cartoon manner is emphasized by the use of the onomatopoeic lettering "WHAAM!" in the right panel, and a yellow-boxed explanation with black lettering at the top of the left panel. The textual exclamation "WHAAM!" can be considered the graphic equivalent of a sound effect.[45] This was to go a feature of his work—like others of his onomatopoeic paintings that contain exclamations such as Bratatat! and Varoom! [46]

Whaam! is i of Lichtenstein'southward series of war images, typically combining vibrant colors with an expressive narrative.[47] Whaam! is very large, measuring one.vii m × 4.0 m (5 ft 7 in × 13 ft four in).[22] It is less abstruse than As I Opened Fire, another of his war scenes.[45] Lichtenstein employs his usual comic-book style: stereotyped imagery in bright principal colors with black outlines, coupled with imitations of mechanical printer'southward Ben-Solar day dots.[48] The utilize of these dots, which were invented by Benjamin Mean solar day to simulate colour variations and shading, are considered Lichtenstein'due south "signature method".[49] Whaam! departs from Lichtenstein'south before diptychs such equally Footstep-on-Tin can with Leg and Like New, in that the panels are not two variations of the same image.[24]

Cropped and edited portion of Drawing for 'Whaam!' (1963). Lichtenstein marked sections of "Drawing" with colour notations for the concluding work, such as the "w" for white in the to a higher place titular letters.[41]

Same portion of finished piece of work, Whaam!, but the planned white letters were xanthous, as rendered to a higher place.

Although Lichtenstein strove to remain faithful to the source images, he constructed his paintings in a traditional fashion, starting with a sketch which he adjusted to improve the composition and then projected on to a canvas to make the finished painting.[50] In the case of Whaam!, the sketch is on ii pieces of paper, and the finished work is painted with Magna acrylic and oil paint on canvas.[30] Although the transformation from a single-panel conception into a diptych painting occurred during the initial sketch, the final work varies from the sketch in several ways. The sketch suggests that the "WHAAM!" motif would exist colored white, although information technology is yellow in the finished piece of work.[41] [42] Lichtenstein enlarged the master graphical subject field of each panel (the plane on the left and the flames on the correct), bringing them closer together as a consequence.[42]

Lichtenstein built upward the prototype with multiple layers of pigment. The paint was practical using a scrub castor and handmade metal screen to produce Ben-Day dots via a process that left physical prove behind.[51] [52] The Ben-Mean solar day dots technique enabled Lichtenstein to give his works a mechanically reproduced experience. Lichtenstein said that the work is "supposed to look like a faux, and it achieves that, I remember".[49]

Lichtenstein dissever the limerick into two panels to split the action from its issue.[24] The left panel features the attacking plane—placed at a diagonal to create a sense of depth—beneath the text balloon, which Lichtenstein has relegated to the margin above the plane.[24] In the right panel, the exploding plane—depicted head-on—is outlined by the flames, accompanied by the bold exclamation "WHAAM!".[24] Although separate, with one panel containing the missile launch and the other its explosion, representing 2 distinct events,[53] the ii panels are clearly linked spatially and temporally, not least by the horizontal smoke trail of the missile.[54] Lichtenstein commented on this piece in a 10 July 1967, letter: "I remember being concerned with the idea of doing two about dissever paintings having little hint of compositional connection, and each having slightly separate stylistic character. Of form there is the humorous connectedness of one console shooting the other."[55]

Lichtenstein contradistinct the composition to make the image more compelling, by making the exploding plane more prominent compared to the attacking plane than in the original.[24] The smoke trail of the missile becomes a horizontal line. The flames of the explosion dominate the right console,[24] but the pilot and the aeroplane in the left panel are the narrative focus.[45] They exemplify Lichtenstein's painstaking detailing of physical features such equally the aircraft's cockpit.[56] The other element of the narrative content is a text balloon that contains the following text: "I pressed the fire control ... and ahead of me rockets blazed through the sky ..."[51] This is amid the text believed to take been written by All-American Men of State of war editor Robert Kanigher.[27] [57] [58] The yellow word "WHAAM!", contradistinct from the cerise in the original comic-book panel and white in the pencil sketch, links the yellow of the explosion below it with the textbox to the left and the flames of the missile beneath the attacking aeroplane.

Lichtenstein's borrowings from comics mimicked their style while adapting their subject matter.[59] He explained that "Signs and comic strips are interesting equally subject area matter. At that place are certain things that are usable, forceful and vital about commercial art." Rebecca Bengal at PBS wrote that Whaam!'s graphic clarity exemplifies the ligne claire style associated with Hergé, a cartoonist whose influence Lichtenstein acknowledged.[threescore] Lichtenstein was attracted to using a absurd, formal style to depict emotive subjects, leaving the viewer to interpret the artist's intention.[50] He adopted a simplified color scheme and commercial printing-like techniques. The borrowed technique was "representing tonal variations with patterns of colored circles that imitated the half-tone screens of Ben Day dots used in newspaper press, and surrounding these with black outlines like to those used to conceal imperfections in cheap newsprint."[59] Lichtenstein in one case said of his technique: "I take a platitude and try to organize its forms to make it awe-inspiring."[51]

Reception [edit]

The painting was, for the most office, well received by fine art critics when first exhibited. A November 1963 Fine art Magazine review by Donald Judd described Whaam! as ane of the "wide and powerful paintings" of the 1963 exhibition at Castelli's Gallery.[35] In his review of the exhibition, The New York Times art critic Brian O'Doherty described Lichtenstein's technique equally "typewriter pointillism ... that laboriously hammers out such moments as a jet shooting down another jet with a big BLAM". According to O'Doherty, the consequence was "certainly not art, [just] fourth dimension may brand it so", depending on whether it could be "rationalized ... and placed in line for the future to assimilate as history, which it shows every sign of doing."[61] The Tate Gallery in London acquired the piece of work in 1966, leading to heated argument amidst their trustees and some song members of the public. The buy was made from fine art dealer Ileana Sonnabend, whose asking cost of £4,665 (£88,842 in 2022 currency) was reduced by negotiation to £three,940 (£75,035 in 2022 currency).[62] Some Tate trustees opposed the acquisition, among them sculptor Barbara Hepworth, painter Andrew Forge and the poet and critic Herbert Read.[62] Defending the acquisition, art historian Richard Morphet, so an assistant keeper at the Tate, suggested that the painting addresses several bug and painterly styles at the same time: "history painting, Baroque extravagance, and the quotidian phenomenon of mass-circulation comic strips."[63] The Times in 1967 described the acquisition as a "very big and spectacular painting".[64] The Tate's director, Norman Reid, later said that the work aroused more public involvement than any of its acquisitions since Earth War II.[65]

In 1968, Whaam! was included in the Tate's first solo exhibition of Lichtenstein's work.[65] The showing attracted 52,000 visitors, and was organized with the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam,[62] which later hosted the exhibition from 4 November to 17 December 1967, earlier information technology traveled to three other museums.[one]

Analysis and interpretation [edit]

For José Pierre, Whaam! represents Lichtenstein's 1963 expansion "into the 'epic' vein".[66] Keith Roberts, in a 1968 Burlington Magazine commodity, described the explosion equally combining "art nouveau elegance with a nervous energy reminiscent of Abstract Expressionism".[67] Wendy Steiner believes the piece of work is Lichtenstein'due south most successful and harmonious comic-based composition. She sees the narrative and graphic elements as complementary: the action and spatial alignment pb the viewer'due south middle from left to right so as to emphasize the human relationship between the action and its explosive consequence. The ellipses of the text balloon nowadays a progression which culminates with a "WHAAM!". The "coincidence of pictorial and exact order" are clear for the Western viewer with the explanatory text beginning in the upper left and action vector moving from the left foreground to the right groundwork, culminating in a graphical explosion in tandem with a narrative exclamation.[68] Steiner says the striking incongruity of the two panels—the left panel appearing to be "truncated", while the right depicts a centralized explosion—enhances the work'south narrative power.[68]

Graphite-pencil-on-newspaper drawing entitled Drawing for 'Whaam!' (1963), xiv.9 cm × 30.v cm (5.9 in × 12.0 in), was donated to the Tate in 1969. Information technology shows the original plan was a single unified piece of work.

Lichtenstein's technique has been characterized past Ernst A. Busche as "the enlargement and unification of his source material ... on the basis of strict creative principles".[59] Extracted from a larger narrative, the resulting stylized image became in some cases a "virtual brainchild". By recreating their minimalistic graphic techniques, Lichtenstein reinforced the bogus nature of comic strips and advertisements. Lichtenstein's magnification of his source textile made his impersonally fatigued motifs seem all the more than empty. Busche also says that although a critique of modern industrial America may be read into these images, Lichtenstein "would appear to have the environment equally revealed by his reference material equally part of American capitalist industrial culture".[59]

David McCarthy contrasted Lichtenstein's "dispassionate, discrete and oddly disembodied" presentation of aerial combat with the work of H.C. Westermann, for whom the feel of military service in World War II instilled a demand to horrify and shock. In contrast, Lichtenstein registers his "annotate on American civilisation" past scaling upward inches-high comic book images to the oversized dimensions of history painting.[two] Laura Brandon saw an attempt to convey "the trivialization of culture endemic in gimmicky American life" by depicting a shocking scene of combat as a banal Cold State of war human action.[69]

Carol Strickland and John Boswell say that past magnifying the comic volume panels to an enormous size with dots, "Lichtenstein slapped the viewer in the confront with their triviality."[48] H. H. Arnason noted that Whaam! presents "limited, flat colors and hard, precise cartoon," which produce "a hard-edge subject area painting that documents while it gently parodies the familiar hero images of modern America."[70] The apartment and highly finished mode of planned brushstrokes can be seen as pop art'south reaction against the looseness of abstract expressionism.[71] Alastair Sooke says that the piece of work can exist interpreted every bit a symbolic self-portrait in which the pilot in the left panel represents Lichtenstein "vanquishing his competitors in a dramatic art-world dogfight" by firing a missile at the colorful "parody of abstract painting" in the right panel.[63]

According to Ernesto Priego, while the work adapts a comic-book source, the painting is neither a comic nor a comics panel, and "its meaning is solely referential and mail service hoc." Information technology directs the attention of its audience to features such as genre and printing methods. Visually and narratively, the original panel was the climactic element of a dynamic page composition. Lichtenstein emphasizes the onomatopoeia while playing down articulated spoken language by removing the voice communication balloon. Co-ordinate to Priego, "by stripping the comics panel from its narrative context, Whaam! is representative in the realm of fine art of the preference of the image-icon over paradigm-narrative".[58]

Whaam! is sometimes said to belong to the aforementioned anti-war genre every bit Picasso's Guernica, a suggestion dismissed by Bradford R. Collins. Instead, Collins views the painting every bit a revenge fantasy against Lichtenstein'southward starting time wife Isabel, conceived every bit it was during their bitter divorce battle (the couple separated in 1961 and divorced in 1965).[72]

Legacy [edit]

Marla F. Prather observed that Whaam!'s yard scale and dramatic depiction contributed to its position equally a historic work of popular art.[71] With As I Opened Burn, Lichtenstein'southward other monumental war painting, Whaam! is regarded equally the culmination of Lichtenstein'southward dramatic war-comics works, according to Diane Waldman.[73] It is widely described as either Lichtenstein'south nigh famous piece of work,[74] [75] [76] or, along with Drowning Girl, as one of his 2 most famous works.[77] [78] Andrew Edgar and Peter Sedgwick describe it, forth with Warhol's Marilyn Monroe prints, as one of the most famous works of pop art.[79] Gianni Versace once linked the two iconic pop fine art images via his gown designs.[80] According to Douglas Coupland, the Earth Book Encyclopedia used pictures of Warhol'south Monroes and Whaam! to illustrate its Pop art entry.[81]

Dave Gibbons created an alternate version of the Novick original with text that parodies Lichtenstein's piece of work.

Comic books were in turn affected by the cultural impact of pop art. By the mid-1960s, some comic books were displaying a new emphasis on garish colors, emphatic sound furnishings and stilted dialogue—the elements of comic book style that had come to be regarded as military camp—in an attempt to appeal to older, college-age readers who appreciated popular art.[82] Gravett observed that the "simplicity and outdatedness [of comic books] were ripe for existence mocked".[27]

Whaam! was one of the primal works exhibited in a major Lichtenstein retrospective in 2012–2013 that was designed, co-ordinate to Li-mei Hoang, to demonstrate "the importance of Lichtenstein's influence, his engagement with art history and his enduring legacy as an artist".[83] In his review of the Lichtenstein Retrospective at the Tate Modernistic, Adrian Searle of The Guardian—who was generally unenthusiastic near Lichtenstein'south work—credited the piece of work'due south title with accurately describing its graphic content: "Whaam! goes the painting, as the rocket hits, and the enemy fighter explodes in a livid, comic-volume roar."[84] Daily Telegraph critic Alastair Smart wrote a disparaging review in which he best-selling Lichtenstein's reputation as a leading figure in "Popular Art's cheeky assail on the swaggering, self-important Abstract Expressionists", whose works Smart said Whaam! mimicked by its huge calibration. Smart said the work was neither a positive commentary on the fighting American spirit nor a critique, but was notable for marking "Lichtenstein'southward incendiary touch on on the U.s.a. art scene".[19]

Detractors have raised concerns over Lichtenstein's appropriation, in that he directly references imagery from other sources[85] in Whaam! and other works of the menstruum.[27] Some have denigrated it as mere copying, to which others have countered that Lichtenstein altered his sources in significant, creative ways.[63] In response to claims of plagiarism, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation has noted that publishers take never sued for copyright infringement, and that they never raised the outcome when Lichtenstein's comics-derived work outset gained attention in the 1960s.[86] Other criticism centers on Lichtenstein's failure to credit the original artists of his sources;[63] [87] [88] Ernesto Priego implicates National Periodicals in the case of Whaam!, as the artists were never credited in the original comic books.[58]

In Alastair Sooke's 2013 BBC Four documentary that took identify in front of Whaam! at the Tate Modern, British comic volume artist Dave Gibbons disputed Sooke's exclamation that Lichtenstein's painting improved upon Novick's panel, proverb: "This to me looks flat and bathetic, to the point of view that to my eyes it's confusing. Whereas the original has got a iii-dimensional quality to it, information technology'south got a spontaneity to information technology, it's got an excitement to it, and a fashion of involving the viewer that this 1 lacks."[27] Gibbons has parodied Lichtenstein'due south derivation of the Novick work.[27] [89]

See besides [edit]

- 1963 in art

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g "Chronology". Lichtenstein Foundation. Archived from the original on six June 2013. Retrieved ix June 2013.

- ^ a b c McCarthy, David & Horace Clifford Westermann (2004). H.C. Westermann at War: Art and Manhood in Common cold War America. Academy of Delaware Printing. p. 71. ISBN978-0-87413-871-ix.

- ^ Busche, Ernst A. (2013). Roy Lichtenstein . Oxford Art Online. Oxford Academy Press]. Archived from the original on xix Oct 2021. Retrieved half-dozen September 2013.

- ^ Lobel, Michael (2002). Image Duplicator: Roy Lichtenstein and the Emergence of Pop Art. Yale University Printing. pp. 32–33. ISBN978-0-300-08762-8.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Minimalism". The Art Story Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Difficult-Edge Painting". The Art Story Foundation. Archived from the original on iii October 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Alloway, Lawrence (1995). "Systemic Painting". In Battcock, Gregory (ed.). Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology. University of California Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN978-0-520-20147-7. Archived from the original on xix October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Chilvers, Ian & John Glaves-Smith (2009). A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. p. 503. ISBN978-0-nineteen-923965-8.

- ^ "Fine art Terms: Fluxus". [Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on eight May 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Pop fine art". The Fine art Story Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- ^ "Appropriation/Pop Fine art". Museum of Modernistic Fine art. Archived from the original on xi Apr 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ^ Stavitsky, Gail, Roy Lichtenstein, and Twig Johnson (2005). Roy Lichtenstein: American Indian encounters. Montclair Art Museum. p. 7. ISBN978-0-8135-3738-ii. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rose, Bernice (1987). The Drawings of Roy Lichtenstein. Museum of Modernistic Art. p. 17. ISBN978-0-87070-416-i.

- ^ a b Lanchner, Carolyn (2009). Roy Lichtenstein. Museum of Modern Art. pp. xi–14. ISBN978-0-87070-770-4. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ a b Thistlethwaite, Marker. "Mr. Bellamy". Mod Art Museum of Fort Worth. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Brown, Mark (18 February 2013). "Roy Lichtenstein outgrew term pop art, says widow prior to Tate show". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved fifteen June 2013.

- ^ Clark, Nick (eighteen February 2013). "Whaam! artist Roy Lichtenstein was 'non a fan of comics and cartoons'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ Schneckenburger, Honnef & Fricke Ruhrberg (2000). Ingo, Walter F. (ed.). Art of the 20th Century. Taschen. p. 321. ISBN978-iii-8228-5907-0. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ a b Smart, Alastair (23 February 2013). "Lichtenstein, at Tate Modern, review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ Pisano, Dominick (2003). Pisano, Dominick A. (ed.). The Airplane in American Civilisation. University of Michigan Press. p. 275. ISBN978-0-472-06833-iii.

- ^ Naremore, James (1991). Naremore, James and Patrick M. Brantlinger (ed.). Modernity and Mass Culture. Indiana Academy Press. p. 208. ISBN978-0-253-20627-5. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ a b Lichtenstein, Roy. "Whaam!". Tate Collection. Archived from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "1960s: Whaam!". Lichtenstein Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d east f g Waldman 1993, p. 104.

- ^ Bacon, James (thirteen May 2013). "Comics and fine art – James talks to Rian Hughes nigh Prototype Duplicator". Forbidden Planet. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Character Sketch: The Comic That Inspired Roy Lichtenstein". Yale Academy Printing. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gravett, Paul (17 March 2013). "The Principality of Lichtenstein: From 'WHAAM!' to 'WHAAT?'". PaulGravett.com. Archived from the original on 27 Baronial 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ "Russ Heath's Comic About Being Ripped off by Lichtenstein". Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Cumming, Laura (29 February 2004). "Whaam! just no Oomph!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ a b "Catalogue entry". Tate Gallery. Archived from the original on 2 Oct 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ Armstrong, Matthew (Autumn 1990). "High & Depression: Modern Fine art & Popular Culture: Searching High and Low". Moma. 2 (6): 4–8, 16–17. JSTOR 4381129.

- ^ "Jet Airplane pilot". Lichtenstein Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 Nov 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Alloway 1983, p. 56.

- ^ "Christie'south to offer a Pop Fine art masterpiece: Roy Lichtenstein's Woman with Flowered Chapeau". ArtDaily. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Judd, Donald. "Reviews 1962–64". In Bader 2009 (ed.). Roy Lichtenstein: October Files. pp. 2–4.

- ^ Marquis, Alice Goldfarb (2010). "The Arts Accept Center Stage". The Pop! Revolution. MFA Publications. p. 37. ISBN978-0-87846-744-0.

- ^ Tomkins, Calvin (1988). Roy Lichtenstein: Mural With Blue Brushstroke. Harry North. Abrams, Inc. p. 25. ISBN978-0-8109-2356-0.

- ^ "Search Result: CRAK!". Lichtenstein Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Lobel, Michael. "Applied science Envisioned: Lichtenstein's Monocularity". In Bader 2009 (ed.). Roy Lichtenstein: October Files. pp. 118–120.

- ^ Lobel, Michael (2002). Image Duplicator: Roy Lichtenstein and the Emergence of Popular Art. Yale Academy Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN978-0-300-08762-8.

- ^ a b c "Roy Lichtenstein: Drawing for 'Whaam!' 1963". Tate Gallery. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d Alley, Ronald (1981). Catalogue of the Tate Gallery's Collection of Modern Fine art other than Works past British Artists. London: Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet. p. 436. ISBN978-0-85667-102-9. as cited in "Roy Lichtenstein: Drawing for 'Whaam!' 1963". Tate.org. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ "Tate Modern opens first major rehang of its Collection with the support of UBS" (Press release). Tate Gallery. 22 May 2006. Archived from the original on ii October 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ "'Roy Lichtenstein: A Retrospective' Debuts At The Art Establish of Chicago (PHOTOS)". The Huffington Post. 22 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Waldman 1993, p. 105.

- ^ "The Study: Mr Roy Lichtenstein". MrPorter.com. 12 Feb 2013. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Alloway 1983, p. 20.

- ^ a b Strickland, Carol & John Boswell (2007). The Annotated Mona Lisa: A Crash Class in Art History from Prehistoric to Postal service-Modern. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 174. ISBN978-0-7407-6872-nine. Archived from the original on 19 Oct 2021. Retrieved 29 Oct 2020.

- ^ a b Churchwell, Sarah (22 February 2013). "Roy Lichtenstein: from heresy to visionary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Illustrated companion". Tate Gallery. Archived from the original on 2 Oct 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013. published in Wilson, Simon (1991). Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion (revised ed.). Tate Gallery. p. 242. ISBN978-0-295-97039-4.

- ^ a b c Monroe, Robert (29 September 1997). "Pop Fine art pioneer Roy Lichtenstein dead at 73". Associated Printing. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ Dunne, Nathan (thirteen May 2013). "WOW!, Lichtenstein: A Retrospective at Tate Modernistic 2". Tate Etc. (27). Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ Archer, Michael (2002). "The Existent and its Objects". Art Since 1960 (second ed.). Thames & Hudson. p. 25. ISBN978-0-500-20351-four.

- ^ Coplans 1972, p. 39: "...Whaam I (1963), on the other hand, is a diptych with a clearly linked pictorial narrative ..."

- ^ Coplans 1972, p. 164.

- ^ Lobel, Michael. "Technology Envisioned: Lichtenstein's Monocularity". In Bader 2009 (ed.). Roy Lichtenstein: October Files. pp. 123–124.

- ^ Gravett, Paul (31 May 2002). "Robert Kanigher: The homo who put Sergeant Stone in a hard place". The Guardian. Archived from the original on xiv March 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Priego, Ernesto (4 April 2011). "Whaam! Becoming a Flaming Star". The Comics Filigree, Journal of Comics Scholarship. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d Busche, Ernst A. (2011). Marter, Joan (ed.). The Grove Encyclopedia of American Fine art. Oxford University Press. p. 158. ISBN978-0-19-533579-eight. Archived from the original on nineteen October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Bengal, Rebecca (eleven July 2006). "Essay: Tintin in America". PBS. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved xix June 2013.

- ^ O'Doherty, Brian (27 Oct 1963). "Lichtenstein: doubtful but definite triumph of the banal". The New York Times. p. 21, section 2.

- ^ a b c Bailey, Martin (13 Feb 2013). "Who opposed a £iv,665 Lichtenstein?". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d Sooke, Alistair (17 July 2013). "Is Lichtenstein a smashing mod artist or a copy true cat?". BBC. Archived from the original on nineteen July 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ "Spectacular piece of Pop art". The Times. No. 56829. three Jan 1967. p. 6, col E.

- ^ a b Holden, Duncan (18 February 2013). "Work of the Calendar week: Whaam! by Roy Lichtenstein". Tate Gallery. Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved xix July 2013.

- ^ Pierre, José (1977). An Illustrated History of Pop Art. Eyre Methuen. p. 91. ISBN978-0-413-38370-9.

- ^ Roberts, Keith (February 1968). "Electric current and Forthcoming Exhibitions: London". The Burlington Magazine. 110 (779): 107–108. JSTOR 875536.

- ^ a b Steiner, Wendy (1987). Pictures of Romance: Grade against Context in Painting and Literature . Academy of Chicago Printing. pp. 161–164. ISBN978-0-226-77229-5.

- ^ Brandon, Laura (2007). Art and State of war. I. B. Tauris. p. 84. ISBN978-1-84511-236-3. Archived from the original on 14 December 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Arnason, H. H. (1986). "Pop Art, Assemblage, and Europe'south New Realism". History of Mod Fine art (tertiary ed.). Prentice Hall, Inc./Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 458. ISBN978-0-13-390360-7.

- ^ a b Arnason, H. H.; Daniel Wheeler; Marla F. Prather (1998). "Pop Fine art and Europe'southward New Realism". History of Modernistic Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography (fourth ed.). Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 538–540. ISBN978-0-8109-3439-9.

- ^ Collins, Bradford R. (Summer 2003). "Modern Romance: Lichtenstein'due south Comic Book Paintings". American Art. 17 (2): 60–85. doi:10.1086/444691. JSTOR 3109436. S2CID 191600665.

- ^ Waldman 1993, p. 95.

- ^ Rice-Oxley, Mark (19 March 2004). "Pop Art'southward one-hitting wonder gets another look". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 9 Baronial 2013.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (ix May 2012). "Whaam! Set to be striking by Roy Lichtenstein's finest comic volume hour". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 Feb 2017. Retrieved 9 Baronial 2013.

- ^ Evans, Mike (2008). Defining Moments in Art. [Cassell Illustrated. p. 515. ISBN978-one-84403-640-0. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 29 Oct 2020.

- ^ Cronin, Brian (2012). Why Does Batman Carry Shark Repellent?: And Other Astonishing Comic Volume Trivia!. Penguin Books. ISBN978-1-101-58544-three.

- ^ Collett-White, Mike (18 February 2013). "Lichtenstein show in UK goes beyond cartoon classics". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on xxx July 2013. Retrieved viii June 2013.

- ^ Edgar, Andrew & Peter Sedgwick (1999). Sedgwick, Peter and Andrew Edgar (ed.). Cardinal Concepts in Cultural Theory. Routledge. p. 190. ISBN978-0-203-98184-nine.

- ^ Brawl, Deborah (2011). Business firm of Versace: The Untold Story of Genius, Murder, and Survival. Crown Publishing Grouping. ISBN978-0-307-40652-1.

He translated one of Roy Lichtenstein'southward almost famous paintings by putting giant letters spelling "WHAAM!" on a yellow clevore evening gown. He adorned a silk halter-neck gown with Andy Warhol's celebrated images of Marilyn Monroe ...

- ^ Teachout, Terry (6 Baronial 2003). "Andy Warhol: xv Minutes And Counting". The Wall Street Periodical. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ^ Brooker, Will (2001). Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon. Bloomsbury Bookish. p. 182. ISBN978-0-8264-1343-vii.

- ^ Hoang, Li-mei (21 September 2012). "Popular fine art pioneer Lichtenstein in Tate Modernistic retrospective". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ Searle, Adrian (eighteen February 2013). "Roy Lichtenstein: also absurd for school?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ^ "Popular Art". Museum of Modern Fine art. Archived from the original on xi April 2021. Retrieved nine Baronial 2013.

- ^ Borrelli, Christopher (11 May 2012). "Connecting the dots on Roy Lichtenstein retrospective at Art Institute: Is appropriation the sincerest form of flattery?". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Steven, Rachael (13 May 2013). "Image Duplicator: pop art's comic debt". Creative Review. Archived from the original on 2 Oct 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ Childs, Brian (2 Feb 2011). "Deconstructing Lichtenstein: Source Comics Revealed and Credited". Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on 12 Jan 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (12 April 2013). "Dave Gibbons Takes on Roy Lichtenstein for the HERO Initiative And Comica". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on ii October 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

References [edit]

- Alloway, Lawrence (1983). Roy Lichtenstein . Abbeville Press. ISBN978-0-89659-331-2.

- Bader, Graham, ed. (2009). Roy Lichtenstein: Oct Files. MIT Printing. ISBN978-0-262-01258-iv.

- Coplans, John, ed. (1972). Roy Lichtenstein. Praeger Publishers. ISBN978-0-7139-0761-2.

- Waldman, Diane (1993). "War Comics, 1962–64". Roy Lichtenstein. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art (Los Angeles, Calif.), Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. ISBN978-0-89207-108-1.

External links [edit]

- Lichtenstein Foundation website

- Tate brandish caption

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whaam!

0 Response to "March 331 1963 Arts of Southern California Xiii Painting"

Post a Comment